Or: How We Learned That “Fully Renovated” Means “We Painted Over the Problems”

Late 2007 – Early 2008

My wife Jennifer and I had been living in NYC apartments for years—the kind where you develop an intimate relationship with your neighbors’ arguments and learn to sleep through sirens like they’re lullabies. We were ready for the opposite: space, quiet, land, maybe even a garage or barn.

Jennifer is an Interior Architect with professional experience in high-profile interiors and product design. She now leads product design for a lighting company. She grew up in a city and wanted the full countryside experience, but more importantly, she lives for details—the kind of architectural details that separate a good house from a great one. The trim profiles, the proportions, the craftsmanship, the way light moves through space. When it comes to design decisions, Jennifer has the final say, and her eye is usually right.

I had my own concerns when looking at houses: What would the renovation costs be? How much of the house bones would need work? What about mechanicals – HVAC, plumbing, electrical? How old were the appliances? I was calculating what we’d actually have to spend to make any existing house livable, and the numbers kept climbing. I also cared about aesthetics and details, but I watched the budget constantly.

We both cared deeply about aesthetics. The difference? Jennifer thought in terms of what would be best, what would look right, what quality required—sky’s the limit. I thought in terms of what we could actually afford while still achieving good design. I tried to find solutions that looked good AND worked well functionally AND didn’t bankrupt us, though I’d occasionally sacrifice looks for practicality or budget when necessary.

This created an interesting dynamic: champagne taste (both of us) on an Old Milwaukee budget (which only I seemed to remember we had). We wanted quality, details, and craftsmanship. We had the budget of two people who’d been saving while living in NYC apartments. Jennifer focused on getting it right. I focused on getting it right within budget.

Spoiler: this tension would define our entire build.

The Market Was Utterly Insane

We started our house hunt in Upstate New York in late 2007, right at the peak of the housing boom. If you weren’t there, let me paint you a picture: every house listing might as well have read “MAKE AN OFFER NOW BEFORE SOMEONE ELSE BUYS IT SIGHT UNSEEN WITH CASH FROM THEIR BEANIE BABY PROFITS.”

The inventory was terrible. Houses that genuinely needed to be gutted—I’m talking houses where you could see daylight through the floorboards and the “vintage charm” was actually knob-and-tube wiring that hadn’t been code-compliant since Eisenhower—were being listed at fully renovated prices.

Our requirements seemed reasonable:

- Commutable to NYC (for work, unfortunately)

- Large piece of property (for Jennifer’s sanity and dreams of not hearing neighbors)

- Character (not 1960s ranch or 1980s split-level with weird angles)

- Within our budget (ahahaha)

What we actually found:

- Overpriced dumps needing $100K+ in work, listed as “charming fixer-upper with potential”

- Nice houses on postage-stamp lots next to highways

- Nice houses on good lots that cost more than we’d make in a decade

- Houses too close to the road (you could wave at passing trucks from bed)

- Houses with not enough land (2 acres is not “estate living”)

- Houses with enough land but the house itself was actively falling down

The Peak Before the Crash

Here’s the thing about timing: we were looking in early 2008, right at the peak before the economic crash. We were shopping at the absolute worst possible moment. But property values didn’t decrease right away—it took months for reality to set in. So we were stuck in this weird limbo where everything was still priced for the boom times, but the boom was actually over and we just didn’t know it yet.

Every weekend we’d drive up from the city, look at houses, meet with realtors who acted like they were doing us a favor by showing us anything, and return home depressed.

“Maybe we should just stay in the apartment,” became our post-house-hunting refrain. “At least when things break here, we call the super and it’s his problem.”

The Style Dilemma

I’d fallen head-over-heels in love with Craftsman-style homes—those 1900s-1920s beauties with exposed beams, built-in cabinetry, art glass windows, and that incredible attention to detail that makes modern construction look like it was assembled by someone reading instructions for a different house.

Jennifer appreciated Craftsman design too—the honesty of materials, the visible joinery, the human-scaled proportions. But she immediately saw the problem I’d missed: we were looking at rural properties—five-acre fields that had been farmland for generations.

“A Craftsman bungalow in the middle of a hayfield?” she said, looking at me like I’d suggested building a Brooklyn brownstone in Montana. “It would look completely absurd.”

She was right, of course. Craftsman style emerged in California and the Pacific Northwest, spreading to suburbs and small-city neighborhoods. Plopping one in the middle of upstate farmland would look like someone had airlifted a house from Seattle and forgot to add the rest of the neighborhood around it.

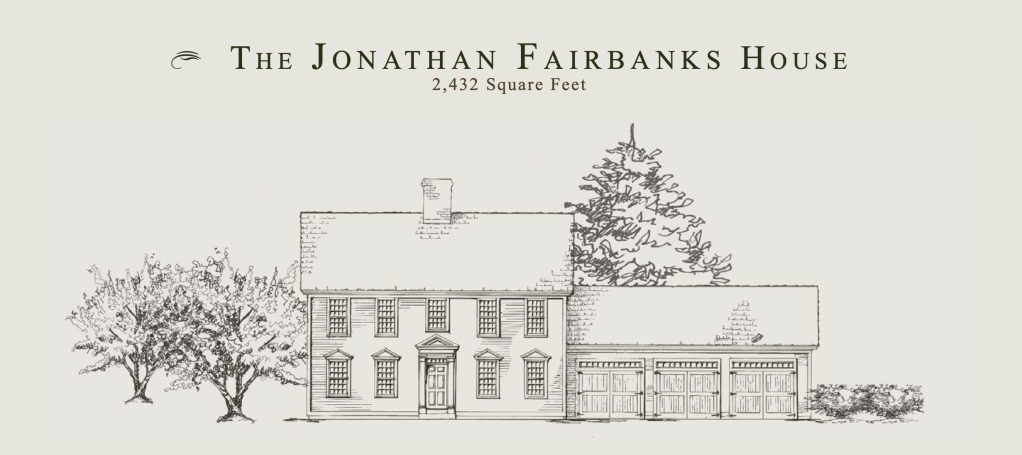

A colonial farmhouse, though? That was authentic to the region and the setting. It would look like it belonged. Get some landscaping established, let a few years pass, and it could look like it had been sitting there since the 1800s. New house, old soul.

Plus, colonials traditionally had the kind of trim detail and proportions that satisfied both our desire for quality craftsmanship and historical accuracy.

This is why you marry an Interior Architect: they save you from your own terrible ideas before you execute them.

The Calculation

Somewhere during month three or four of soul-crushing house tours—after seeing our fifteenth house that “just needs cosmetic work” (translation: the foundation is crumbling but we painted the walls)—we did the math.

Buy an overpriced house that needs work: $X + $50-100K in renovations + living through renovation hell + inheriting someone else’s hidden problems.

Buy land and build new: $X + controlled costs + no surprises + getting exactly what we want.

On paper, building made sense. We weren’t naive—we didn’t think building would be easy. We thought it would be better. More cost-effective. More controlled. You know exactly what you’re getting. No surprises hidden behind walls. No “oh by the way, the previous owner used the crawlspace as a home for raccoons.”

We thought building would be hard work. We just didn’t realize how hard, or that “no hidden surprises” would be replaced by “constant visible surprises.”

“We can do this,” Jennifer said, looking at the numbers. She’d managed major construction projects professionally, coordinating with contractors, architects, engineers. “We know what goes into building. We can be our own general contractors and save money there.”

She was right that we could do it. She was wrong about the “save money” part. Well, we saved money on the GC fee. We spent it all on mistakes, therapy, and developing a very dark sense of humor.

I loved the idea of a kit house—controlled factory construction, historical details, quality materials. Like those Sears catalog homes from the early 1900s, but modern. Efficient!

“How hard could it be?” I did not ask, because I’m not an idiot.

What I thought was: “It’ll be hard, but manageable.”

What it actually was: “Hard in ways we couldn’t have imagined, manageable only by the loosest definition of that word.”

Reader, we were optimistic. Not naive, but optimistic. And optimism, it turns out, is just ignorance wearing a smile.

The Decision

We officially gave up on finding an existing house. We were going to buy land and build.

We’d get Jennifer’s large property where she could look out and not see another house. We’d get the level of detail and craftsmanship we both wanted. We’d get exactly the floor plan we wanted. We’d have everything new—new systems, new appliances, nothing that needed immediate repair or updating.

There was just one small problem: we both wanted high-quality details and materials, but we had very different relationships with the budget. Jennifer’s professional background meant she knew exactly what quality looked like and what it should cost—and in her mind, you don’t compromise on quality. My practical side meant I worried constantly about what we could actually afford and how to achieve what we wanted within our constraints.

Jennifer thought sky’s the limit. I knew we had a ceiling, and it wasn’t very high.

We were not uber-wealthy clients. We were two people who’d saved diligently while living in NYC apartments. Champagne taste on an Old Milwaukee budget.

This would prove… interesting.

But first, we needed to find land. And I needed to track down companies that made kit houses with all the historical architectural detail we both wanted.

That’s when I discovered Connor Homes in Vermont.

What We Got Right (Yes, Really)

Before we move on to Part 2, let me say: giving up on the existing housing market in early 2008 was actually the right call. Those overpriced houses? Many of them lost 30-40% of their value over the next two years. The market was absolutely insane, and we were smart not to buy into it.

Building was the right decision for us. Having Jennifer’s professional expertise meant we’d at least make informed mistakes rather than ignorant ones.

How we built it, though? Well, that’s the next 21 blog posts.

__________________________________________________

Next up: Part 2 – Kit House Dreams: Discovering Connor Homes

(In which we find a catalog of beautiful historical kit houses, Jennifer starts designing in CAD, and we learn that “kit” doesn’t mean “easy,” it just means all your problems arrive at once in a truck)

__________________________________________________

Quick Takeaways

What We Did Right:

- Recognized an overheated market

- Walked away from bad deals

- Had clear vision of what we wanted (thanks to Jennifer’s professional expertise)

- Had an Interior Architect on the team who actually knew what she was doing

- Were willing to consider alternatives

- Matched style to setting and regional vernacular

- Understood building would be hard (just not *how* hard)

What We Got Wrong:

- Thought we could achieve Jennifer’s professional-grade standards on our budget

- Underestimated the gap between “hard” and “holy-shit-what-have-we-done”

- Believed “new” meant “maintenance-free”

- Thought acting as our own GC would save money (it did, but we spent the savings on mistakes)

- Didn’t account for the champagne taste / Old Milwaukee budget problem

For Anyone House Hunting Today:

- Don’t buy at the peak if you can avoid it

- “Fully renovated” needs to be verified, not trusted

- Factor in TRUE renovation costs (double what they tell you)

- If you’re going to build, have clear vision of what you want

- Professional design expertise helps avoid basic mistakes

- Understanding aesthetics ≠ having budget to match your standards

- When both partners care about quality, budget becomes even tighter

- Style should match your setting and regional vernacular

- Building isn’t easier than buying, it’s just different-hard

- GC fees exist for a reason

- Sometimes the best house is the one you build

- Sometimes the best house is the one you keep renting

- We were definitely the former, but we might have been the latter

Leave a comment