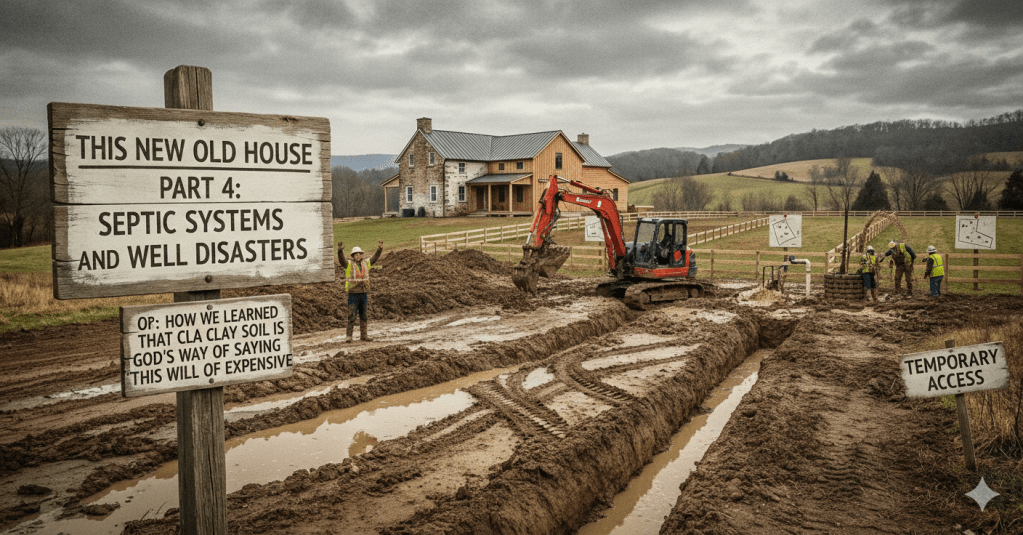

Or: How We Learned That Clay Soil Is God’s Way of Saying “This Will Be Expensive”

Beginning Summer 2009

With our land purchased and our house design finalized, it was time to deal with the unglamorous but absolutely critical underground infrastructure. When you’re building off the municipal grid, you need two things before you can even think about a foundation: somewhere for water to come from (a well) and somewhere for it to go (a septic system).

This seemed straightforward. People have been digging wells and managing waste for thousands of years. How hard could it be?

(I really need to stop thinking that phrase.)

The Perk Test from Hell

Before you can install a septic system, you need a percolation test—a “perk test”—to determine how well your soil drains. The health department wants to know that when you flush your toilet, the wastewater will actually, you know, percolate through the soil rather than just sitting there creating a biohazard.

Our soil was clay. Heavy, dense, beautiful orange-ish clay that holds water like a grudge.

The perk test results came back, and the septic guy looked at us with the expression of someone delivering bad news about a terminal diagnosis.

“You’re going to need an above-ground system.”

“What does that mean?” I asked, already knowing I wasn’t going to like the answer.

“It means we build a mound. Truck in sand, build up the leach field above grade. It’s the only way to get proper drainage with your soil.”

Jennifer and I looked at each other. We were thinking the same thing: How much is this going to cost?

The answer: A LOT more than we’d budgeted.

The Above-Ground Reality

An above-ground septic system is exactly what it sounds like: instead of burying your leach field in the ground where it belongs like civilized people, you build a giant sand mound in your yard and put the leach field in that.

The costs add up fast:

- Excavation

- Truckloads of proper sand (not just any sand will do)

- Engineering the mound

- The actual septic components

- Installation

- Praying it all works

We knew it would be expensive. Like everything else, it cost more than expected.

What we budgeted: $X

What it actually cost: Significantly more than $X

The system went in. A giant mound now dominated part of our yard—our future “hill where the grass dies every summer” (more on that later).

The Tank Depth Problem

Here’s something we should have thought about but didn’t: when your leach field is above ground, it affects how deep you can bury your septic tank.

Our tank ended up very close to the surface—maybe a foot or two of coverage. This has pros and cons:

Pros:

- Easy to access for maintenance

- Pumping every 5 years costs only $400-500

- You can find it easily

Cons:

- The grass above it dies every summer from heat

- It looks bad

- You’re very aware of where your waste is going

- Limited grading options around it

We also wanted minimal foundation showing on the house (Jennifer’s preference for aesthetics), but we’d already spent our grading budget on the septic mound. We couldn’t afford to truck in unlimited amounts of fill. Towns also have codes limiting how much you can grade.

So we made compromises. Looking back, I’d have budgeted $5,000-7,000 more for final grading and proper topsoil. But hindsight is 20/20, and our budget was what it was.

The Toilet Paper Incident

Five years after moving in, I went to the basement one day and found water on the floor.

This is never good.

I traced it back to the sewage line. We had a clog. A SEWAGE clog. In a house with two small children who were still learning bathroom independence.

I called a septic company. The technician came out, inspected the situation, and started laughing.

“What?” I asked, not seeing the humor in sewage water in my basement.

“Your older kid uses a lot of toilet paper, doesn’t he?”

How did he know?

Turns out, my three-year-old son was using approximately half a roll per bathroom visit. Because our foundation was at a certain depth and our leach field was above ground, there was limited slope from the house to the septic tank. This meant that giant wads of toilet paper—instead of flowing smoothly into the tank—were getting hung up at the tank inlet where there’s a diverter.

“Common issue,” the septic guy said, still amused. “Easy fix. I just break off the plastic diverter.”

“You… break it off?”

“Yep. Don’t need it anyway if it’s causing problems.”

He broke it off, pumped the tank, and charged me. We’ve had the tank pumped once more since then (kids are big poopers, figuratively and literally), but no more backups, thank goodness.

Important lesson: If your kid clogs every toilet they use, name a plunger after them. We did.

The Salt Water Revelation

During that service call, the septic guy mentioned something else: “Your water softener backwash—that’s not running into the septic tank, is it?”

“…yes?” I said, suddenly worried.

“Yeah, you don’t want that. The salt can corrode the junction boxes and cause failures. Should have its own drainage line.”

Great. Another thing we should have done but didn’t.

What we should have done: Run a separate drainage line for the softener backwash during initial plumbing.

What we actually did: Let it drain into the septic and hoped the salt wouldn’t destroy everything immediately.

Drilling the Well

While septic was happening, we also needed water. You need water on-site fairly early—for construction, for getting your certificate of occupancy, for, you know, living.

We hired a well driller and asked where he recommended drilling. He walked the property, did whatever mystical divining well drillers do, and picked a spot the appropriate distance from where the septic would go.

“I’ll charge you by the foot until we hit the water table,” he explained. “Could be 100 feet, could be 500. Won’t know until we drill.”

We gave him the go-ahead and tried not to think about the per-foot costs adding up.

At about 250 feet, he called.

“We hit water, but it’s not producing enough flow to stop. I can keep drilling, or I can frack it.”

“Frack it? Like… fracking? For oil?”

“Similar concept. We’ll use hydraulics to open up the fissures in the rock to increase flow.”

“How much does that cost?”

He told us. It was less than drilling another 200 feet and hoping.

“Frack it,” we said.

It worked. Our well produced adequate flow. But in hindsight, this may not have been the best choice. We still get large sediment in the first of our many filters (oh yes, there are many filters—we’ll get to that).

Question I should have asked: “Will fracking increase sediment in my water?”

Answer I would have received: “Probably, yes.”

The Water Test

To get your certificate of occupancy, you need a lab to test your well water and certify it’s safe. The lab gives you specific instructions involving flushing the system with bleach and following a precise protocol.

We followed the steps. The water passed. We celebrated.

What they don’t test for: how your water will actually perform in daily use. Hardness? Sulfur smell? Iron content? That’s all on you to figure out.

The Well Runs Dry (Temporarily)

Later, after we’d moved in and were trying to establish a lawn, I had two sprinklers running for hours. The well ran out.

“Wells can run out?” I asked the well guy when I called in a panic.

“Sure. They’re not meant to run continuously for hours. Also don’t use them to fill swimming pools, even small ones. The water will start to run cloudy—that’s your warning.”

Good to know. Wish I’d known it before I nearly burned out the pump.

Tomorrow’s Problem: The Filter Saga

We had water. We had septic. We were ready to build.

What we didn’t know yet: the water filtration nightmare that awaited us. The iron. The sediment. The sulfur. The hard water deposits. The seven different filters we’d eventually need. The untrustworthy local “experts.” The trial and error that would span years.

But that’s a problem for later in the build.

For now, we had underground infrastructure. It worked. Sort of. At great expense.

__________________________________________________

Next up: Part 5 – Water Wars: The Filter Saga

(In which we discover that “the water tested fine” and “the water is fine” are very different things, and that I’ll eventually become an accidental expert in residential water treatment through sheer desperation)

__________________________________________________

Quick Takeaways

Septic Systems:

✅ DO THIS:

- Get the perk test early

- Budget 50% more than estimates for above-ground systems

- Account for extra grading if you need above-ground

- Run salt-water backwash to separate drainage (not septic)

- Know where your tank access is

- Plan to pump every 5-10 years ($400-500)

- Budget $5,000-7,000 for final grading and topsoil

❌ AVOID THIS:

- Assuming any soil will work for in-ground

- Skimping on grading budget

- Letting softener salt water go into septic

- Forgetting that above-ground = visible mound

- Not planning for tank access

- Having kids who use half a roll of toilet paper per visit (just kidding, you can’t control that)

Well Drilling:

✅ DO THIS:

- Budget by the foot (it’s always deeper than you hope)

- Ask about sediment if they recommend fracking

- Follow lab testing protocols exactly

- Size your pressure tank generously

- Plan for filtration from day one

- Understand well limitations (not for continuous running)

❌ AVOID THIS:

- Running sprinklers for hours non-stop

- Filling pools from your well

- Assuming “water tested clean” means no treatment needed

- Trusting that first-day water quality will last

- Installing the softener before understanding your water issues

Budget Reality:

- Above-ground septic: $15,000-25,000+ (vs. $8,000-12,000 in-ground)

- Well drilling: $8,000-15,000 depending on depth

- Water treatment: $500-5,000 (or more, as we’ll discover)

- Final grading: $3,000-7,000

- Topsoil: $1,000-3,000

Add 30% to all estimates. Seriously.

What Actually Matters:

Looking back, the above-ground septic mound doesn’t bother me. The grass dying in summer is annoying but minor. What matters: having water that works and waste that goes away. The rest is just expensive learning experiences.

What We’d Do Differently:

- Budget more for grading from the start

- Run separate line for softener backwash

- Ask better questions about well fracking and sediment

- Plan for water filtration from day one

- Accept that we both wanted champagne aesthetics on an Old Milwaukee budget, but only I was watching what things actually cost

Our Grade: C+

It works. It cost too much. We made it harder than it needed to be. But 15+ years later, we still have water and functional septic, which is the ultimate measure of success.

Leave a comment